Should You Stop Pitching Your Manuscript as Women’s Fiction?

What We’re Talking About When We Talk About Women’s Fiction

I was intrigued when I opened Jane Friedman’s paid newsletter yesterday and found an article entitled, “The Women’s Fiction Dilemma: A Contested Label Continues to Sell Books” by Sangeeta Mehta. I was particularly eager to read more as I’ve been bumping into this lack of certainty around women’s fiction more and more lately. I had just finished a meeting with a writer I’ve been working with since her initial story idea who is now polishing her manuscript and working on her pitch package. Recently we prepped for live conference pitches, which she nailed—each agent was very intrigued and she got manuscript requests from all four. We were thrilled!

But one small point had ruffled me…each agent pushed back on calling her story women’s fiction, suggesting she should be pitching it strictly as upmarket or book club fiction. I don’t disagree that it fits into those categories—it certainly does—but I was a little surprised by their vehemence and balking at women’s fiction.

I have another client who has also written a fantastic manuscript and recently live pitched, as well. She, too, received multiple manuscript requests, and also was emphatically advised by the agents to avoid calling it women’s fiction.

If you’re a women’s fiction writer, you know that women’s fiction has been a contentious term for a while. Not only is it controversial (Because why women’s fiction only? Why the need to separate women from general fiction?) but it is also tricky to understand what qualifies as women’s fiction and what does not. Even with the oft-referenced definition1 by the Women’s Fiction Writers Association (of which I am an active member), it’s just not as clear cut as, say, a thriller or a mystery.

But this appeared to be something new…not contention around the usage of the term, not confusion around what constitutes women’s fiction and what does not. The newsletter article alluded to agents and editors steering away from pitching books as women’s fiction, which aligned with my authors’ recent experiences.

Interviewed for the newsletter, the legendary literary agent Carly Watters is quoted as saying, “In my experience, editors are not positioning books as women’s fiction right now.” (Watters is also responsible for creating the incredibly helpful Do You Know the Difference Between Literary, Upmarket and Commercial Fiction? infographic ten years ago.) Her sentiment was echoed in the article by others. Zibby Books’ executive editor, Kathleen Harris, said she sees the terms book club fiction or relationship fiction used more than women’s fiction these days. Literary agent Jessica Sinsheimer (and co-founder of Manuscript Wish List®) was even quoted as saying most of the agents she knows now say book club fiction instead of women’s fiction.

As you probably know, in 2022 Publishers Marketplace removed women’s fiction as a category in its announcements of publishing deals. However, women’s fiction continues to be a BISAC (Book Industry Standards and Communications) category, which is how publishers, retailers and libraries categorize books for the purposes of marketing, selling and generally getting them into the hands of readers.

I’ve been analyzing the women’s fiction debut deals as well as recently published women’s fiction titles over the last few months, so I knew we were still seeing plenty of women’s fiction titles published but I decided to take a closer look at the data. In January through June 2025, there were 171 books published2 (or slated for publication in the next couple months) that list women’s fiction as the primary BISAC code. Books can have multiple BISAC codes, but the primary BISAC code is supposed to be the most specific and accurate. There were many more books that listed women’s fiction as a secondary or tertiary code.

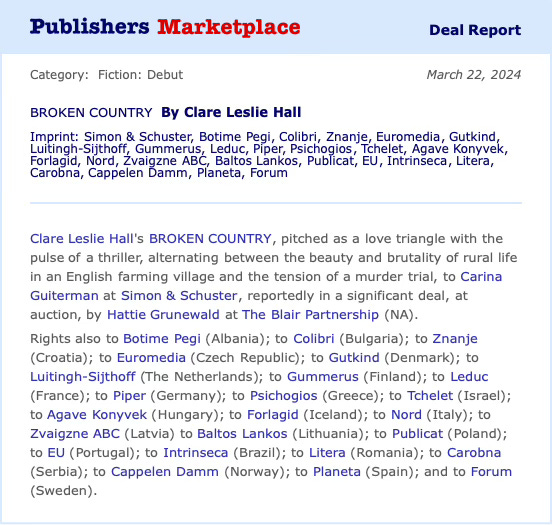

However, you might not guess that if you read the initial deal announcements in Publishers Marketplace (PM). Take the eagerly awaited Broken Country by Clare Leslie Hall (March 4, 2025), which the PM announcement called “a love triangle with the pulse of a thriller.” The final marketing copy reinforces this: “A love triangle unearths dangerous, deadly secrets from the past in this thrilling tale perfect for fans of The Paper Palace and Where the Crawdads Sing.” Yet neither romance nor thriller is indicated in the BISAC codes; the sole code listed for the title is women’s fiction. (If you’re curious, The Paper Palace has a primary code of women’s fiction, and Where the Crawdads Sing has a primary code of literary and a tertiary code of women’s fiction.)

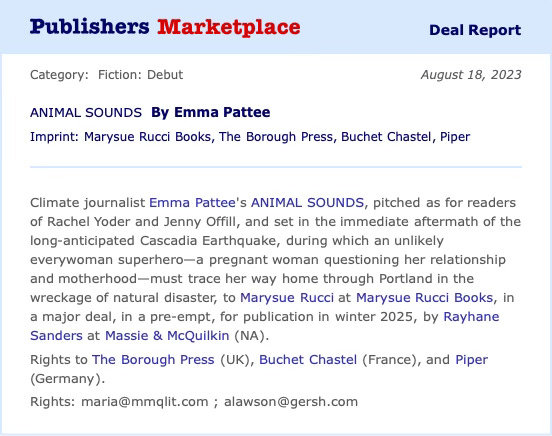

Another highly anticipated book, according to GoodReads’ “Readers' 84 Most Anticipated Books of Spring,” is Emma Pattee’s debut, Tilt (March 25, 2025), which the PM announcement said was pitched for readers of Rachel Yoder and Jenny Offill. Yoder’s acclaimed Nightbitch has a primary BISAC code of women’s fiction, but also secondary codes of family life and satire. Offill’s last two books (Weather and Department of Speculation) both list the primary BISAC code as literary fiction and a secondary code as psychological fiction. Only one BISAC code is listed for Tilt: women’s fiction.

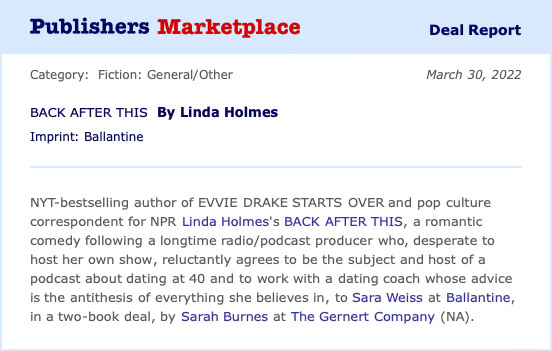

The PM announcement for author Linda Holmes’s second book, Back After This (February 25, 2025), calls the story a romantic comedy, yet the final BISAC codes show the primary code as women’s fiction with romcom listed as the second code, which, if you remember, should make it not as precise as the primary code.

What does this all mean? Titles might be pitched to publishers as one genre then marketing copy might focus on a different (though related) genre or subgenre, and the books might be categorized in still another genre. One can see why writers continue to be confused when it’s time to query agents.

To return to those 171 titles I mentioned above…of these, only 23 percent (40 books) listed women’s fiction as the sole BISAC code. Frequent supplementary BISAC codes included: Family Life (54), Romance (49), Literary (23), Historical (20), Friendship (15), and Humorous (12). Lest you think there’s no way only 20 historical fiction books were published in a six-month period (and you would be right!), to confuse matters, historical fiction (and many other subgenres) has its own BISAC code. And many titles you might consider historical fiction and women’s fiction show up with a primary code of historical fiction, or even only a historical fiction code. A quick, non-scientific count showed about 50 additional titles categorized primarily as historical fiction that could also be categorized as women’s fiction.

You know what’s not a current BISAC code? Book club fiction or upmarket fiction. Neither upmarket nor book club fiction are Publishers Marketplace categories either. I also searched PM to see if any of the 2024-25 deals mentioned either of these within the announcement copy. In 2025, there was one title called upmarket (a debut upmarket thriller), and three in 2024. No titles at all are referred to as book club fiction in the announcements either year. (Although there are a handful of books with “book club” in the title because, it seems, we still love to read about reading).

Yet clearly we are still reading and buying and, yes, writing women’s fiction. I am currently the co-chair for the Women’s Fiction Writers Association’s Rising Star Awards, and WFWA is going strong. And, remember, the 171 titles I mention above do not even include the many titles that list women’s fiction as a supplementary code. So, how’s an aspiring women’s fiction writer to make sense of it all?

In Jane’s newsletter, Mehta advises writers “might do better to avoid using the term women’s fiction on its own in a query.”

My personal take is that I can’t help but notice that the terms agents seem to prefer now are much more specific than women’s fiction. In my analysis of 2024 women’s fiction debut deals, I noted that the 164 titles encompassed a wide variety of the signature elements of personal growth and relationships: family dynamics (32 debuts), marital issues (14 debuts), sisterly relationships (11 debuts), mother/daughter relationships (10 debuts), friendship (22 debuts), and romantic themes (20 debuts). And, of course, there are many additional themes: we saw historical fiction, coming of age, and magical realism, stories inspired by real people and real-life events, and stories that take on larger social issues like gender equity.

Maybe this trend we are seeing of avoiding pitching as women’s fiction emerged as a way to better clarify where a title falls. Because a book like Holmes’s very fun Back After This is lighthearted and funny, which differs greatly from, say, another highly anticipated spring release, Good Dirt by Charmaine Wilkerson, a multigenerational epic steeped in tragedy. Yet both have a primary BISAC code of Fiction/Women.

Perhaps the broadness and confusion around women’s fiction has industry folks finally saying, could we be a little more specific about what we’re talking about when we talk about women’s fiction, please? In the newsletter, both Watters and Harris emphasize the importance of using strong comps in queries to do the heavy lifting of signaling who your book will appeal to. So is this really about clearer positioning in a competitive marketplace? That certainly benefits authors and readers alike.

We also see this supported in the publishers’ marketing categorization as 77 percent of the aforementioned titles published in the first half of 2025 with a primary women’s fiction BISAC code also include supplementary BISAC codes that provide additional info about the book. In other words, less than a quarter of the titles are labeled only as Fiction/Women.

It seems pitching authors would do well to follow suit by getting as precise as possible in their queries: First, zeroing in on a more specific subgenre or, if applicable, the trend of genre-blending. Perhaps for you that will mean using upmarket or book club or coming of age or something else altogether. You might want to review Watters's infographic (linked above) as well as the extremely helpful Genre Guide: Women’s Fiction, Upmarket, Romance, Literary…? by author and book coach Lidija Hilje to better determine where your story fits. Second, selecting really solid comps that can signal the audience your title will attract.

But also…keep in mind this is about market positioning, not about what you should be writing. I’m a big believer in keeping the reader in mind as you write, but that’s never about writing to trends and always about ensuring your story will connect with readers on the page. Writers should continue to write the stories of their hearts because authentic writing will never go out of style.

Pitching authors, I’d love to hear from you! What are your experiences of pitching a women’s fiction story? Are you using another genre in your query? Please share in the comments!

Heather Garbo is a certified book coach, editor and writer with a background in communications, book publishing, and nonprofit work. Heather specializes in working with women’s fiction writers who are discovering (or rediscovering) their writing voice in midlife. Find her at www.garbobookcoaching.com.

Note: This post contains affiliate links, which means if you purchase a book by clicking on that link, I may earn a small commission.

The Women’s Fiction Writers Association defines it as this: “Women's Fiction is a layered story in which the plot is driven by the protagonist’s emotional journey. Women’s Fiction can encompass a wide range of genres, including speculative, mystery, contemporary, science fiction, and more, and can be set in any time period.” https://www.womensfictionwriters.org/

As available to order through Edelweiss, the digital platform that hosts all major U.S. publishers, including 95% of the U.S. frontlist. Note this number includes initial publication of titles only, so titles that originally debuted as hardcover and were then released as paperback were not included in this total.

I just signed with an agent — and she referred to my book as upmarket. While I was querying I knew it could be upmarket, book club, or women’s fic and I took the lead from the agents MSWL and used the language they did in my queries because in my research it seems like those categories are often interchangeable. I was stressed in the beginning of my query process because of that genre question. But in a class I took in Kauai the agent teaching the course told us all that most querying authors get their genre wrong, that your agent will help you figure it out and to not sweat it as much 🤣 I still stressed a little :)

A terrific analysis! Thank you for dissecting the deals and BISAC codes.